I’ve recently become very active on Bluesky after having finally accepted that Twitter was dead, and it’s been wonderful to escape the din over on the dead bird, and re-engage with people who love books, and reading, and libraries, and who value education and kindness.

This morning, I saw a post on Bluesky (apparently they are called “skeets” but I am not sure I’m quite ready for that…) by an Australian English teacher in which he mentioned preparing to teach Gerard Manley Hopkins’ gorgeous poem “Spring and Fall”, which gives us the immeasurably beautiful phrase “Goldengrove unleaving”:

Márgarét, áre you gríeving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?

Leáves like the things of man, you

With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?

Ah! ás the heart grows older

It will come to such sights colder

By and by, nor spare a sigh

Though worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie;

And yet you wíll weep and know why.

Now no matter, child, the name:

Sórrow’s spríngs áre the same.

Nor mouth had, no nor mind, expressed

What heart heard of, ghost guessed:

It ís the blight man was born for,

It is Margaret you mourn for.

I fell in love with this poem as an undergraduate English Lit. student at Macquarie Uni in the 1980s, the same institution that gave me my great passion for children’s literature when I returned there as a young English teacher to do post-graduate studies. It’s probably no real surprise to find that there are many resonances of Hopkins’ poem in children’s books, given its subject matter, but I like the synergy.

And because this is true — “Spring and Fall” is a poem that speaks to the great matter of so much of the canon of children’s literature, the passing of the various seasons of childhood — it was no surprise to see a mutual of the original poster and I, the author Jessica Friedmann, recommend to him Lois Lowry’s first children’s (or what we would now call young adult) novel, A Summer to Die, which quotes the poem in context of the death of the protagonist’s sister. (I of course followed that recommendation up with one of my own, to Jill Paton Walsh’s duology Goldengrove/Unleaving, and so the spiral continues…)

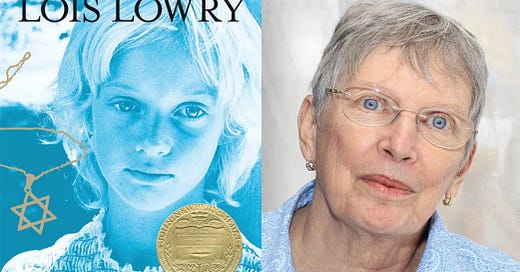

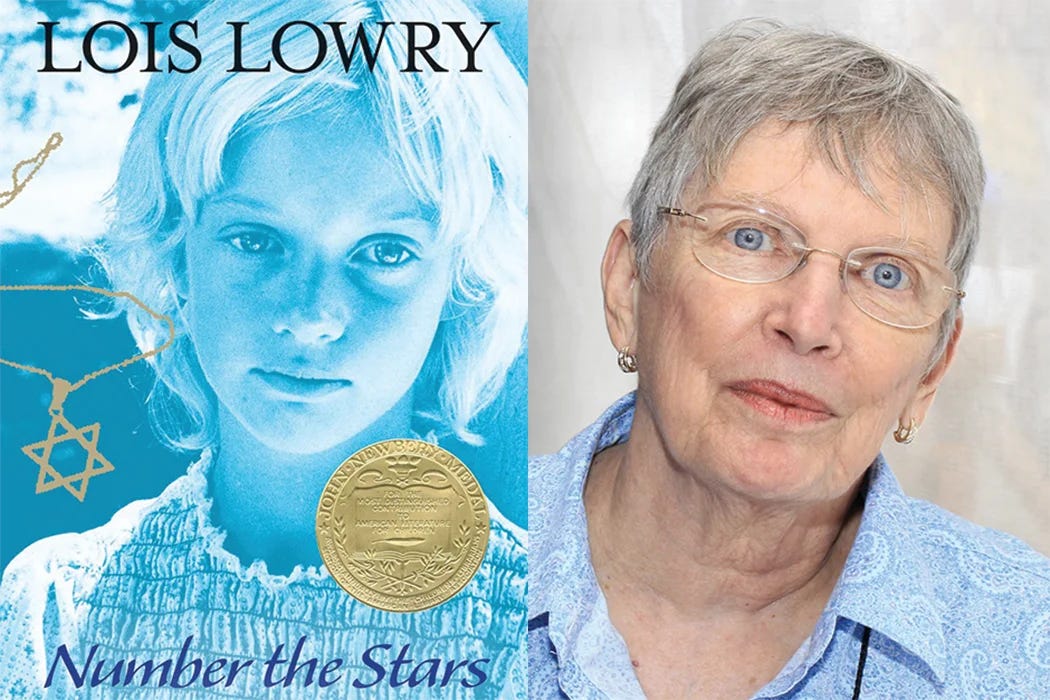

Lowry is best-known these days for her novel The Giver and its sequels, classics (especially the first) of their genre, and a staple of English book rooms all over the English-speaking world (and perhaps beyond). I admit I was a bit puzzled when I returned to teaching after many years doing other things, to find that my colleagues chose it as an “easy” book for less-engaged readers. It’s not a book I would ever have characterised as easy, given its deeply serious subject-matter, but it seems as if it was well-received by those students, so perhaps it doesn’t matter how it’s characterised. But I digress…

Back on Bluesky, Jessica added a link to Lowry’s 2011 May Hill Arbuthnot Lecture to the thread, which I took time out to read this morning and am so grateful to have come across. (The Arbuthnot Lecture is, or was, an annual lecture organised by the American Association for Library Service to Children, a branch of the American Library Association. It is named for May Hill Arbuthnot, a teacher, editor and writer who was a leading force in children’s literature studies in the mid-20th Century. There is no-one listed as having given the lecture since 2020, so I don’t know if it still exists. The speakers over the years include writers for young people, academics, critics and others with a specialist knowledge of the field. The only Australian to have given the lecture was Patricia Wrightson, in 1985, and if anyone can track down her speech for me, I’d be eternally grateful!)

Lowry’s speech is a beautifully crafted journey through her writing life, weaving together stories of her parents and of her own parenting, of how she devoured learning and literature when she returned to college after her children were older (she married at 19!), stories of tattoos and poetry and grief, and of how the loss of her sister, and an overture from a children’s publisher, led her to write A Summer to Die, and all the children’s and young adult books that followed.

At the heart of the essay is the why of children’s literature.

And I just love how she expresses this.

A letter from a reader, who came across the Hopkins poem in A Summer to Die, and who writes to tell Lowry that’s she, the reader, is getting the words of the poem tatooed onto her body, remind Lowry of another poem, “There Was a Child Went Forth” by Walt Whitman, which begins:

There was a child went forth every day,

And the first object he look'd upon, that object he became,

And that object became part of him for the day or a certain part of the day,

Or for many years or stretching cycles of years.

This is what books do. In a series of anecdotes, Lowry recounts how children absorb knowledge, and culture, and so much more, from the books they read. It is delightful for us word-nerds and pop culture afficionados and those of us who value shared cultural references to read these anecdotes and think, perhaps smugly, that of course, reading is pragmatically a good thing because you learn from it. And of course you do. I used to say to my students in the English classroom that I corrected their pronunciation and so on so they wouldn’t embarrass themselves at parties, and that was partly true. I also told them that I wanted them to be able to use language well so they would have power in their lives. I was quite explicit about this: the better you can express your ideas the better you will be able to stand up to a boss, or a boyfriend, who is treating you badly, the better you will be able to defend yourself and others. Language is power, and so too, as the aphorism goes, is knowledge. And reading gives you access to that.

And children’s books DO acculturate their readers. There’s no getting away from that, and why would we want to? We do learn all kinds of useful and arcane knowledge from the books we read, including secondhand exposure to other writers and books. And all of that is excellent, if very middle-class, except of course working-class children also need access to that knowledge if they want to have power in this world, and books are to my mind the most efficient way of passing that knowledge and therefore power on. But as we have seen in the past two decades or millennia, however you want to frame it, it has to be about more than power. And again, a writer has told us that.

More from Lowry’s essay. She’s talking about an encounter with her nephew, an aspiring playwright:

Our conversation digressed, then, because we had family gossip to catch up on, but had we continued talking about the writer’s need to take it all down…I think we would have agreed that our need is not just for the recording of things, but also for the finding of the meaning of things, and the connections (and here I’ll quote not James, but Forster: Only connect! Everyone recognizes that phrase, but so few people recall its context: Forster said: Only connect the prose and the passion, and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its height. Live in fragments no longer). The connections, the making sense of things, the giving meaning to things…and then the giving of all of it to readers….that is the passionate need of the writer.

The didactic view of children’s books I flirt with a couple of paragraphs above is an entrenched one, and one that in my early, passionate, evangelical years, or maybe decades, of working in a space dedicated to advocacy for children’s literature, is one that I also largely rejected. I hated the idea of children’s books as being merely educative, because I had never experienced reading that way — except that of course, I had. I just didn’t see what I was learning because I was too involved in the pleasure. I suspect that is true of many of us “reading children”, and it wasn’t until I was much older and had more perspective that I saw how much I had learned from all that reading, and how powerful that was. And that it wasn’t just about sumptuary laws in mediaeval England from all those Jean Plaidy novels, or the dangers of ring-barked trees courtesy of Judy Woolcot’s tragic fate. It ran much deeper than that, to those connections that Lowry writes about so eloquently in the quote from her lecture above. So yes, I found out about the streets of the upper west side of Manhatten from Harriet the Spy, but I also learned about friendship, and loneliness, and trust and betrayal and what price you might pay to be true to yourself, and to write, from Harriet M. Welsch (and Louise Fitzhugh) as well.

The world is making me feel very dispirited and without hope right now, and it’s frankly made me question what I do, and why I bother doing it. I really needed to read Lois Lowry’s essay today. Perhaps you do too.

Oh, and Lois? I remember Rabble Starkey. Pretty sure she’s sitting on the shelves in my shed where all my most treasured children’s books are, the ones I couldn’t get rid of when I moved three thousand miles last year. I’m going to go and re-acquaint myself with her now.

H Judy - Thanks for this! I have a long essay about A Summer to DIe that I keep trying to finish - my sister and I swapped the book during lockdown - it had been one of the first books passed between us sisters that I remember ...your links aren't working for me for some reason but I'm wondering if they're to Lowry's list of speeches on her website. There's a beauty there where she talks about 'making herself up' through books (and how her older sister didn't need to'. This resonates with me so deeply! I also learned lots of poetry through children's/YA books - including S.E Hinton & Paul Zindel ... I guess it's the same today just that the objects being referred to are different - more likely to be films/games etc ....

This is beautiful, Judith. I just read The Giver for the first time this week because I saw that it’s a banned/challenged book in the US. The writing and the story made me curious about the author, so your lovely essay (with the welcome link to Lowry’s speech) comes to me like a gift. Thank you.