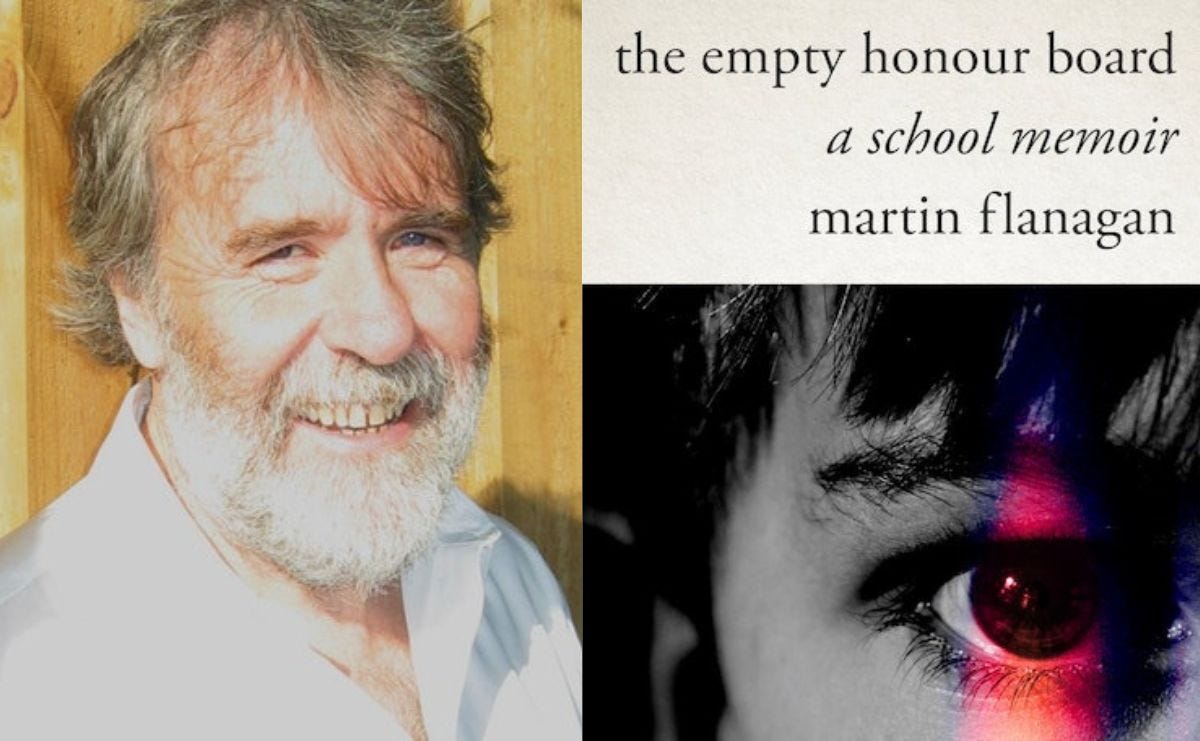

Over the last few days, I have been listening to the audio book of Martin Flanagan’s book The Empty Honour Board: A School Memoir. It tells the story of his years at a Catholic boys’ boarding school in the 1960s, and the experience of many of his contemporaries of sexual assault at the hands of some of the clerical teaching and residential staff. I want to return to my wider thoughts on this book soon, as it had quite a few resonances for me, not (thankfully) because of the SA, but because when I was 22, and fresh out of university, I was appointed to a boarding school, one of only two public boarding schools in NSW, where I was required to live in as a “house parent”. At 22. And some of the girls I was supposed to be in loco parentis for were only a handful of years younger. In the book, Martin, who, along with his wife Polly, I have come to know since I moved to Launceston, asks for people to share their stories of boarding school with him, and I would like to do that. It was a hell of a year.

But before I do that, I want to get down my thoughts on another matter that Martin’s book caused me to reflect upon. In my recent post about the AATE/ALEA Conference in Hobart, I wrote about my presentation on “text selection for reader engagement in the English classroom”. A significant part of the presentation was asking teachers to reflect on why we continue to teach certain books, and one of the books I specifically mentioned was William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. It’s a book that spoke deeply to Martin about his experience at school, which ironically is where he read it, as much for its depiction of bullying and the power games and destructive behaviour of the boys in the book and the boys at his school as it was about the SA. Although of course those things can’t be neatly separated out. Martin returns to consider Lord of the Flies several times during the memoir, which he describes as the “novel which had first impressed itself upon (my) consciousness” when he read it at age 14 (so, circa 1969):

What I read made perfect sense to 14-year-old me. For years, I carried in my mind a scene near the end where Ralph, the character who attempts to preserve civilised standards, feels a black weight descend on his mind. It’s actually a bit more complex than that in the book, but that’s how I recalled it over many years. Why? Because a black weight descended on my mind when I was 13; only the black weight wasn’t ultimately caused by something someone did to me. It was caused by something I did to someone else.1

There’s no denying the power a book can have on an individual when it speaks to you at a critical moment in your life, and there’s certainly no denying the life-long impact of the first book to impress itself upon your consciousness. Later in the memoir, Martin writes about his affinity for Ralph:

“I got his dimly understood belief in civilised standards of behaviour, I understood the black shadow of depression that ‘flutters’ on his brain, so too his faltering sense of reality under escalating stress.” He also acknowledges that while he recognises the bullying behaviour of Jack, he also acknowledges that “In defence of the old school, however, I do want to say that I never saw a single bully dominate the whole place like Jack did. Not nearly. Nor did I see, as happens in movies (including, I think, the 1963 film version of Lord of the Flies), a whole group of kids with a uniform intent of causing hurt. What I saw was a couple causing hurt and, on the faces of the rest, doubt and uncertainty as they realised it would take Jesus Christ to stop what was unfolding before their eyes and Jesus Christ wasn’t present.”2

Despite that, I have to admit I read these passages about Lord of the Flies a little wryly, because Lord of the Flies is one of the books I singled out in my AATE presentation, when I asked people to consider why we continue to teach the same canon-ised novels over years and decades. I chose it as an exemplar, not because I think it’s a bad book, or that it shouldn’t ever be taught again, but because it represents a long-standing trend in the teaching of English (so I guess that means it’s not really a trend, but a feature), and the selection of texts for the English classroom, that focus on the worst of human nature. (And, dare I say it, these texts tend to be from the male point of view.)

Here is my presentation slide featuring Lord of the Flies, which came after I asked the audience to consider the following question:

Why do we continue to teach texts that subsequent scholarship, research, or responses from the relevant community tell us present problematic representations of specific groups of people, of history, and of human nature, and which do real damage to living people?

I’m not the first person to ask this question. There has been lots of discussion among English teachers for some time now about the mood and tone of the texts privileged by curriculum committees. Students and parents complain about the relentlessly bleak outlook of many of the set texts, particularly in the senior years, but by no means exclusively. I think our cultural privileging of these texts is both complex and also pretty obvious. Drama is privileged over comedy. Romance literature is dismissed as “chicklit”. Fantasy that doesn’t strictly adhere to the Campbellian-patriarchal order is questioned (and while I’m not a fan of the books myself, let’s just consider the cultural baggage that goes along with the new genre classification of “romantasy”).

I also referenced Ursula Le Guin in my presentation, and her amazing Pilgrim acceptance speech when she won the Science Fiction Research Association award for Lifetime Achievement in the field of science fiction scholarship in 1989:

I remember also having a long, difficult and at times upsetting conversation with a colleague about why we continue to teach texts that glorify (or perhaps worse, dismiss) violence against women. The text in question was Browning’s “Porphyria’s Lover”, but it could just as easily have been Of Mice and Men, or Othello for that matter. And yes, I know we also teach The Colour Purple and The Handmaid’s Tale, but the canon definitely favours the male POV and male writers, and anyway, my larger point is this:

Why do we continue to focus on texts that reflect the worst of human nature and impulse, and treat those that celebrate love and friendship and community as somehow less worthy?

So as I read Martin’s memoir, and his reflections on Lord of the Flies, I remembered these various conversations and debates, and then began to ponder on another aspect of my presentation, which was about revising our view on using Young Adult (YA) literature in the classroom. I’ve always been an advocate for this, and I have found great success in teaching substantial, thoughtful, and yes, literary (however you might personally define that most slippery of terms) YA fiction to teenagers. Books like Kate Constable’s Crow Country, Claire Zorn’s One Would Think the Deep are two examples from the last decade of my time in the classroom. And perhaps ironically, neither of these are what you would call entirely cheerful novels. Both deal with big themes of racism, violence (domestic and otherwise), as do other YA novels popular with English teachers. I think this is partly to do with the overall privileging of drama over comedy, but it's also I think due to the way English teaching has often been too-“issues” focused, and has been since at least the 80s, when I started teaching.

But here’s the difference. Every children’s and young adult writer I have ever met and spoken with and heard at conferences and festivals — and that’s a bloody lot of people over my long career — no matter how disparate they are in genre, temperament, writing style, personality, ego and talent — they all have something in common. They all believe at the heart of their being that books for young people can be anything, can be about anything, but they must all have hope. Here’s an example of this belief from Australian YA author Shivaun Plozza. There are numerous others; you’ll find it in books on writing for kids and teens and a thousand other places.

I’ve long held the opinion—a widely shared opinion I think—that literature for young people should always end with hope, with a sense that the world goes on and that the chance to make it better is always within our reach. To be honest, it’s not an opinion I’ve ever thought deeply about; I just accepted it as a given, like the grass is green and the sky is blue.

Schools today are very different places from when I first started teaching in the mid 80s. Student well-being is front and centre. Trauma-informed practice is becoming the norm for teachers, and I support all of this. And I’m not saying we should avoid difficult topics, or the darker side of humanity, and I’m not a big fan of trigger warnings in the sense that I think we might have in some respects become too risk averse. Art is meant to trouble us. But I do think we should balance out the world view we offer students through the books we give the imprimatur of study-worthy and culturally important to.

I’m not sure why it took so long for me to think about it in these terms, but for the first time, I began to think about the deep irony of the fact that the books that by nature of having been written for the very people sitting in front of us in the classroom contain hope are often the books that are derided as unworthy of our scholarly approbation. What are we really trying to say to students about the world if what we are showing them through the vehicle of literature is that the world is grim, dangerous, and unforgiving?

I’m going to leave the final word to Martin, although I’d like to hear your thoughts in the comments. Towards the end of The Empty Honour Board, Martin describes being invited by a friend in San Francisco to zoom into his classroom of 14 year olds in 2020 to talk about Lord of the Flies. And it gave Martin some cause to re-reflect on the book that had been so formative to him as a young person. It’s the kind of reflection I think is important that all of us who value the role of literature in young people’s lives should do as part of our regular practice:

Lord of the Flies does represent a depressing view of human nature. What I said to the 14-year-olds is that it’s only one view. Want another? Read Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. Read Abraham Lincoln’s second Inaugural Address. William Golding’s novel doesn’t explain Abraham Lincoln. It doesn’t explain Weary Dunlop or Patrick Dodson, it doesn’t explain Rinso [a student 13-year-old Martin witnessed being beaten up by another boy and in which beating he did not intervene] or Tim [one of Martin’s brothers, who also attended the school], it doesn’t explain my wife and lots of other women I’ve met . . . life’s about balance.3

Flanagan, Martin. The Empty Honour Board Penguin Random House Australia, 2023 p. 14

Flanagn, p. 185-186

Flanagan, p. 188

I am not trained enough in literature to comment knowledgeably about this, but it has gotten me thinking. I remember when I was young, I read "difficult" literature in school, but I was a big reader of less worthy works outside of English class. My children were the same. In elementary school, they read Number the Stars, but outside of school, they gloried in Babysitter's Club books. I wonder if they need both (and everything in between).

I have largely quit my local book clubs, because I thrive on children's books and they only read kids' books for the Holiday Season, when they need lighter fare and books for gifts for children. I don't understand why children's books are considered "lighter" fare. The best of them stay with us for years.

I think many things.

* too many texts are selected ONLY because they are "classics" and seem to have little relevance to students or their lives, often very unsuitable in terms of themes for High School students

* In NSW many texts selected for our HSC make no actual sense. One would think texts that have won various prizes been widely recognised as relevant would be selected. All too often it is out of print or small publisher texts no one has ever heard of. More than once the question has been raised how out of touch those selecting must be and dare i say what do they gain from the many left field selection.

* Y.A fiction is an immense blessing and a deep burden at the same time. Often engaging very able readers who never really move on to adult fiction this limiting themselves.

* Many. many life enhancing books never get a look in and are never considered.

* The constantly diminishing time allowed to teachers to read widely in the Y.A genre. By the end of my career i simply did not have the time to read any new Y.A fiction, too many hours working.

* The immense political pressure both from the department of education and from activist parent groups made many, many relevant texts absolute no go zones and are increasingly removing many texts from libraries.

* Finally the drive to improve reading in primary education is paying off, we are getting a much better level of competent readers into High School. Sadly most of them see reading as work and only do it when compelled.

And yes text selection remains a massive and serious issue to be considered.